Quantum computing, encryption and cyber security - explainer

What could quantum computers mean for cybersecurity and encryption, and what should we do about it?

Quantum computing has the potential to transform the future of computing. While they won’t provide a generic speed up for all types of calculations, there will be some specific problems where quantum algorithms will provide a significant advantage. In particular, certain calculations that are just impossible to do with current “classical” computers may become feasible with quantum computers. As well as providing new opportunities, this capability can also create risks in the hands of an adversary. One such risk, often talked about, is the cyber security threat, in particular to some of the modern encryption that we rely on. But what really is the threat, and what should we be doing?

(While I’ve tried to keep this deep dive non-technical, it is quite lengthy; if you’re time poor, feel free to skip to the conclusions in the final paragraph!)

First, we need to recognise that ensuring the cyber security of our digital world relies on many things, but one component is encryption of data. Traditionally, dating back to the pre-digital age, we normally relied upon “symmetric encryption”, where the same key is used to encrypt and decrypt the data. This relies on the sender and receiver finding some way to securely share such a key without anyone else being able to eavesdrop on the exchange - generally involved trusted parties meeting in person.

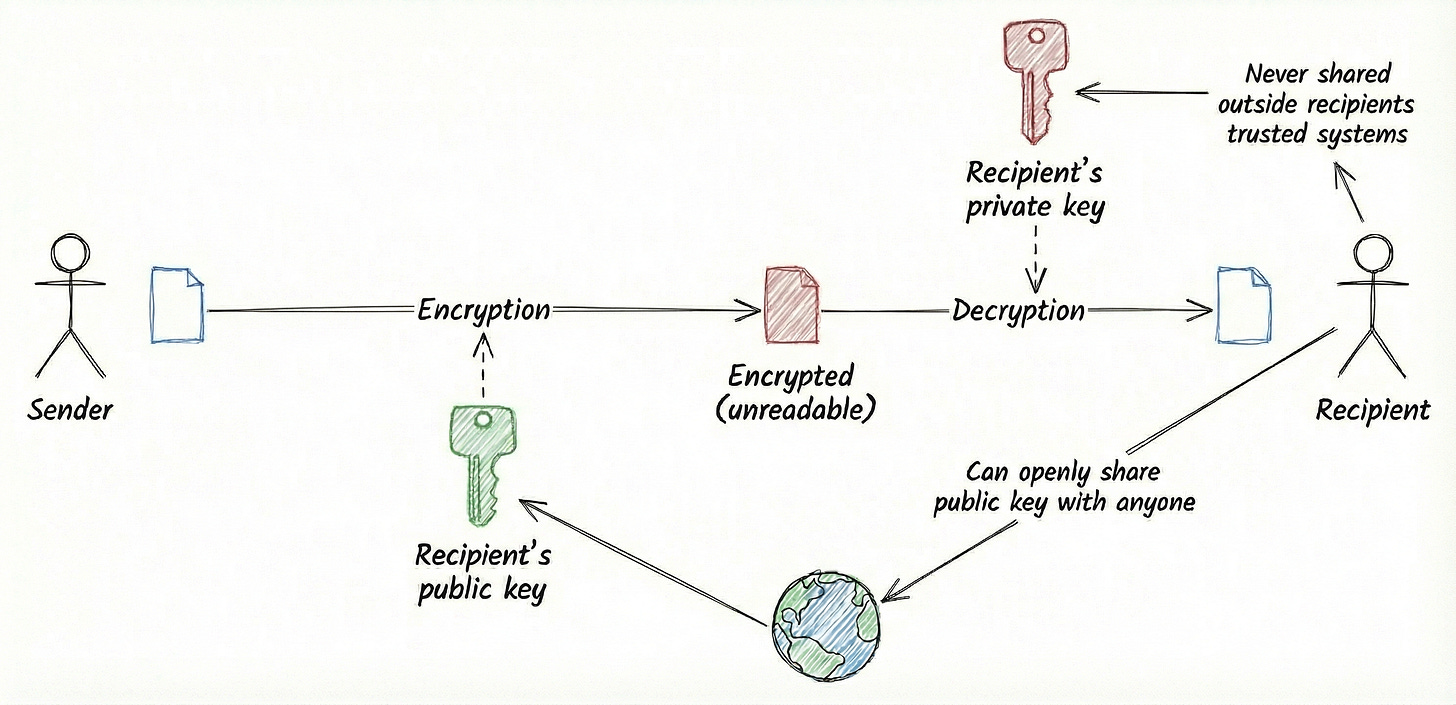

With the advent of the internet, and the desire to communicate with parties all over the world that we’ve never met in person, a different solution is needed. This is known as “asymmetric encryption”, or “public key cryptography”. It requires a special scheme that allows two different keys to be used - a public key that can be shared with anyone, and a private key that is just kept by one person and never shared. Data sent across the network that is intended for this person can be kept private from other prying eyes. This is by using a scheme that encrypts the message with the public key, but can only be decrypted using the private key - so no-one other than the private key holder can view the data being sent.

It should also be noted that the reverse of this process can be used for verifying the sender of a message (authentication) - the sender encrypts agreed data using their private key; anyone can decrypt this “digital signature” using the corresponding public key and if they recover the agreed data this proves the sender must have encrypted it using the correct private key.

This whole concept of public key cryptography relies on some clever maths, sometimes called a “one-way” function, that is easy to calculate in one direction (convert private key to public key) but difficult to reverse (work out the private key from the public one). The security of both the encryption and authentication relies on the assumption that is effectively impossible (using currently available computers) for anyone to work out the private key from the public key. The main methods currently used to secure data sent across the internet, such as RSA, rely on functions such as multiplying together two large prime numbers1 - very easy to do, but it is very difficult to work out from the answer what the original two prime factors were, especially if they were very large numbers. Note, however, that we can’t actually prove the difficulty of reversing the calculation - but over 30 years on from when this was first proposed, no-one has found any effective way to do so (or if they have, it’s a very well-kept secret!).

However, it turns out that this sort of factoring problem is one that quantum computers appear to be quite good at. In 1994, Peter Shor proposed an algorithm (Shor’s algorithm) that could be used on a sufficiently large quantum computer to do just this. Latest estimates are that using this to attack modern encryption schemes used on the internet, such as RSA-2048, would need around 2,000 effectively “perfect” qubits that could run for several days without errors. Today’s best quantum computers have only a few hundred qubits that have errors every few seconds, so there is a long way to go, and certainly no realistic threat today.

However, as quantum computers get better, we can be progressively less confident in our assumption that it is almost impossible for someone to work out the private key from the public key if we rely on these sort of prime factoring type of problems. This in turn means that we can be less confident that when we send data over a public network that someone on the network can’t read the content. We might also worry that someone could collect the data sent across the network today, and could decrypt and read at some point in the future when they have a large quantum computer - sometimes called the “harvest now, decrypt later” threat. The quantum computer could also be used to forge a digital signature; however, signatures are normally verified at time of use, so a future quantum computer is unlikely to affect trust in signatures used today.

This suggests we need to find some alternative type of public-key encryption, but how urgent is the need for change? Although the threat may be a long way off, anyone involved in IT projects knows that upgrading lots of different systems that communicate with each other will be a multi-year projects. Also, for cases where harvest now, decrypt later is a threat, there will also be an urgency to protect data as soon as possible.

There are some fancy other quantum technologies that have been proposed to secure data sent across networks, but by far the easiest solution would be to find some different maths, with a one-way function that we believe cannot be easily reversed using a quantum computer (or today’s computers, of course!). If we have different maths that we can run on current hardware, this will be a much more straightforward solution, normally just requiring software upgrades.

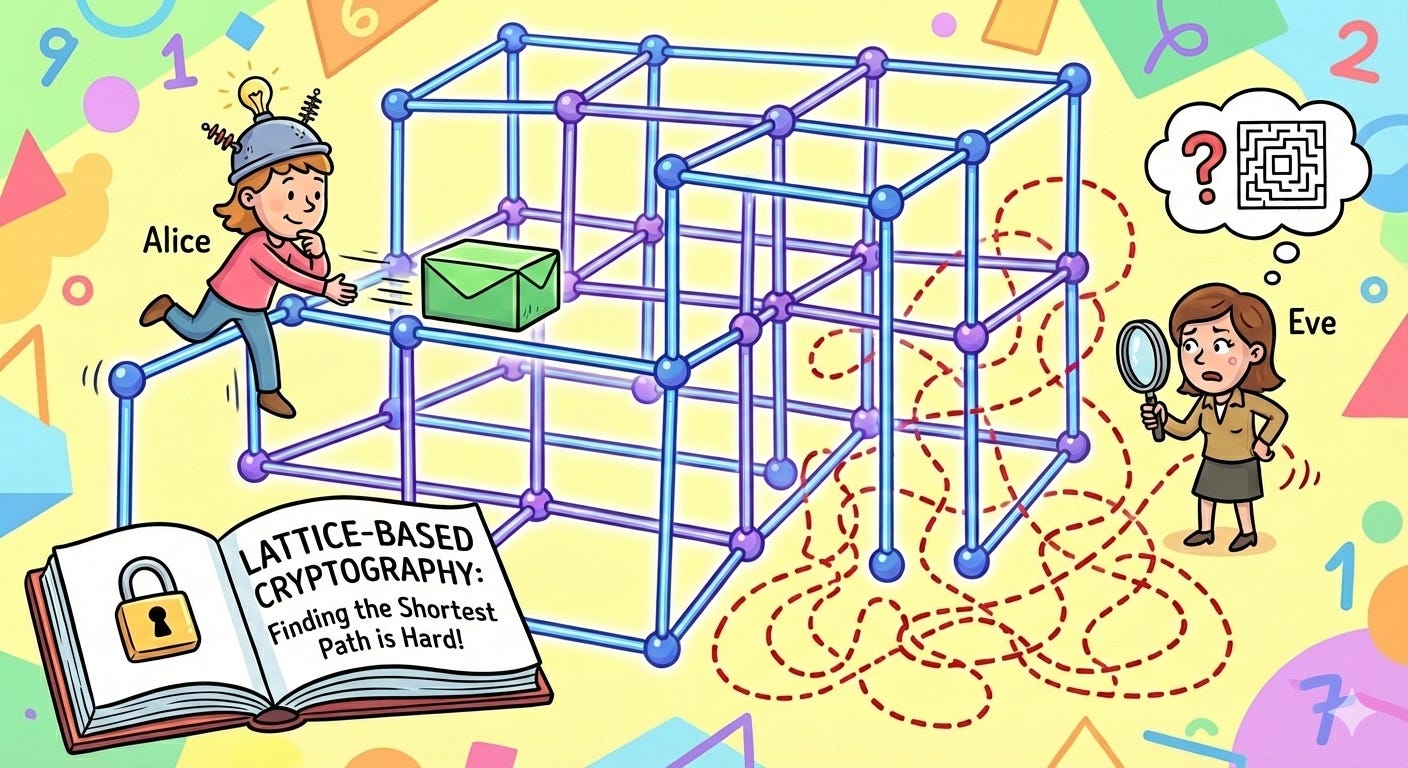

Fortunately, people have anticipated these quantum threats since Shor’s algorithm was first published, and have been working on developing such different maths for many years - often referred to as “post quantum cryptography” (PQC) or “quantum resistant cryptography” (QRC)2. The most significant effort has been by NIST, the US-based standards organisation, which ran a public competition over several years to define new cryptographic standards. This culminated in the approval in late 2024 of three new standards, mainly based on a mathematical concept called “lattice-based cryptography” (This unfortunately doesn’t have a nice simple explanation, so I won’t try!)

It should be noted that we can’t actually prove the lattice-based cryptography is safe from being attacked by a classical or quantum computer - in the same way that we can’t prove that RSA can’t be attacked by a classical computer. However, we do have the confidence that, over almost 10 years of the NIST competition, no-one has found and published any effective attacks - whereas vulnerabilities were disclosed for some of the other candidates that were considered and therefore discarded. So, at least for now, we can have confidence in the NIST standards.

Now that the new cryptographic algorithms have been finalised by NIST, work is starting to implement them. They are being included in some of the other standards that define how the internet works, and software vendors are starting to include them in their latest product updates. Co-ordinating updates across different systems and vendors will take time but ultimately should be straightforward for most cases.

Initial concerns that lattice-based encryption might require more computing power appear to be unfounded, although the new schemes do require longer keys which can increase network traffic. This could be a challenge for some small embedded systems with limited memory and/or limited communication bandwidth, so some specialised systems may require new hardware, but this will be the exception, not the rule. There will also be challenges with systems that were not designed to be software-upgradeable, and where the vendors are no longer around to maintain the system.

Therefore, the overall migration to PQC/QRC will have a long tail of a small number of systems that are going to be difficult to upgrade. Some of these difficult systems may also be the most critical, so a risk-based approach will be needed to work out where to prioritise action.

We should also note that the work to develop PQC algorithms is still ongoing. NIST is standardising some other algorithms in order to provide more options, and fallbacks if lattice cryptography is found to be vulnerable at a later date. Some countries are also developing their own national standards as an alternative to the US-backed NIST proposals, in particular China. Even here in Australia, the Government has recently funded an academic centre of excellence to continue research and build sovereign capability in cryptography, as this will be a core tenet of trust in digital systems into the future.

If you remember nothing else….

In conclusion, quantum computers could threaten the assumptions we currently make about encryption - standards such as RSA and ECDH that we use to protect data sent across networks from being read by others, and how we verify who is sending data. Realising this threat will require significant advances in the capabilities of quantum computing from where we are today. However, if someone had such a device, they could potentially read data without us knowing about it - the only way we might realise is by inferring from any actions they take based on such knowledge. Given this uncertainty, the long times to migrate to new types of encryption, and the potential threat of data being collected now and decrypted later, work on addressing this threat should start now. Fortunately, a solution exists, called “post quantum cryptography” (PQC) or “quantum resistant cryptography” (QRC). Despite the name, PQC/QRC doesn’t actually require anything quantum. This is a good thing as we can start implementing it today, although we need to be aware it is a developing field.

Future articles in this series will dispel some of the common myths around this topic, both in terms of the actual risk and the potential solutions, and will then go on to look at how organisations can start taking practical action.

MDR Quantum helps organisations to understand and assess their quantum risk and to respond accordingly. Our services include executive briefings, policy development, risk assessment and PQC migration strategy and planning - please reach out if you’d like to learn more about how we may be able to help.

This is the basis of how a common scheme called RSA encryption works, Nowadays we also commonly use “discrete logarithms” and “elliptic curves” (using schemes known by names such as Diffie-Helman, ECDH etc), where the maths is more complicated to explain, but turns out to be fairly similar in terms of the difficulty of reversing the calculation, except when using a quantum computer.

The terms PQC and QRC are interchangeable and each has their own advocates; however, it’s important to avoid confusing alternative terms like “quantum cryptography”.

Fascinating. This piece articulates the core challenge of post-quantum cryptography with admiraable clarity, especially for a non-technical audience. Your point on specific problem advantages, rather than generic speed-ups, is crucial. It’s a nuanced but vital distinction often overlooked in popular discussions about the future of computation. Very well put.