Myth-busters: quantum risks to encryption and cybersecurity

Understanding what quantum computing means for cybersecurity is important, but misinformation and confusion abound, and can be dangerous

Quantum technology is an exciting subject with massive potential, but it is also plagued with misunderstandings and misconceptions. The impact of quantum computing on encryption is no exception to this. However, it is a topic that most organisations need to understand, even if they are never likely to use a quantum computer. So, to help organisations make the right decisions, it’s time to bust some of the most common myths. Since there are so many out there, we’ll start with myths about what the actual risks are - myths about potential solutions will be a future post!

I’m going to dive right in, but if you’re looking for a general introduction to the topic of the impact of quantum computing on encryption, see my earlier primer. I’m also going to skip over what might be the biggest myth, that a “cryptographically relevant quantum computer” that could actually be a serious threat to any current encryption already exists or is imminent - since that was also covered in an earlier article.

Note that all these myths have appeared in some form from sources that might be considered reputable - such as major tech vendors, big brand consulting firms, and even Government documents. However, you can be fairly sure that anyone using them doesn’t really understand the subject and/or is trying to sell you something you probably don’t need.

Myth 1: All encryption is at risk

Quantum computers can’t just magically break any encryption, simply because they don’t try all solutions at once, but instead use specialised algorithms to solve very specific problems. So those apocalyptic visions of all security failing and the meltdown of the world are just plain wrong. The main risk is to asymmetric (public key) cryptography which relies on specialised mathematics known as “hidden subgroups”. The easiest example to understand for a non-mathematician is finding the prime factors of a large number. Actually, all you need to know is that if you see anything using encryption such as RSA, Diffie-Hellman (DH) or Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), then those are the systems that could be vulnerable to attack by a quantum computer.

Typically, these types of encryption are used to protect data sent across a network where we are worried an attacker might be able to see this, and for digital signatures, where we want to verify who has sent particular information across a network. These are important security measures for some systems, so quantum computers could still be a major threat for those cases, but not for everything.

In particular, “symmetric” encryption which relies on some sort of shared secret key or password, not some sort of public/private key exchange, is not vulnerable to quantum computer attack.

Myth 2: “Q-Day” is coming

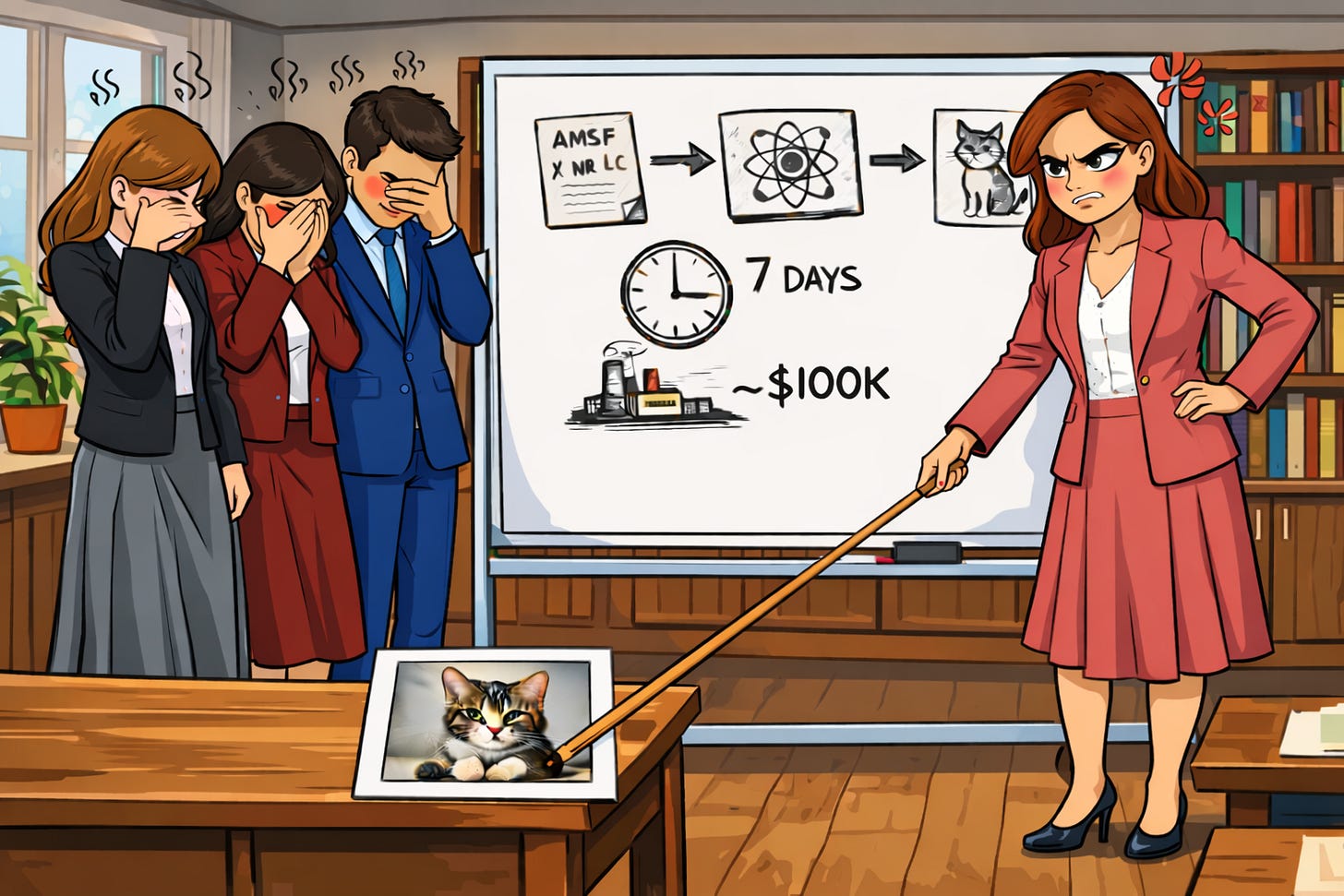

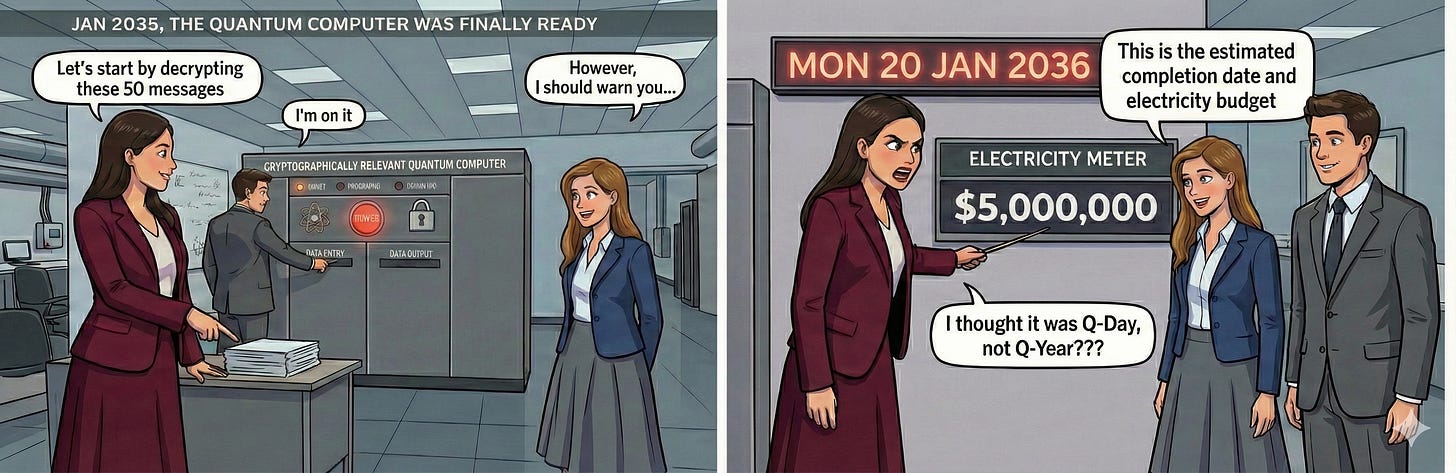

Another common theme in some of the dramatic narratives is the concept of “Q-Day” - some mythical day when a quantum computer comes along, and suddenly every bad actor can see everyone else’s data. Even if we remember myth 1 and narrow this to every attacker being able to see everything sent across the internet, it’s still just not true. The first quantum computers that can threaten modern encryption, such as RSA 2048, will be very big and very rare. They will also be very expensive, not only to build but also to run. The electricity cost to recover a single session key for a single captured session will probably be over $100,000, and it will take about a week to run1. So anyone who has one of these devices will be very selective about what they use it for.

Of course, over time such devices will probably become smaller and cheaper, so more people will have access and can use them to attack more transmissions, but it will be a case of the risk gradually increasing over time, not a single day when everything changes. The danger of the Q-Day myth is that it suggests a single deadline to upgrade everything, and so it distracts from the importance of assessing the risk of different systems, and using this to prioritise where to start work on upgrading encryption2.

Myth 3: Your risk is related to the data that your organisation stores

When armchair pundits start trying to give advice on quantum cybersecurity threats, they often seem to lapse into suggestions like “reviewing sensitive data holdings”. At this point, we should recall Myth 1 - not all encryption is at risk. When protecting stored data, encryption is normally only one of a number of security measures that should be implemented. However, even this encryption is normally symmetric encryption based on a stored key, which, as we’ve seen is not vulnerable to attack by a quantum computer.

The quantum threat is therefore nothing to do with the data that you store - what you need to consider is what data you send across a network that an attacker may be able to see. If this encryption uses a quantum-vulnerable public key cryptographic algorithm, then it may be at risk - so this is the data that you need to assess for the harm caused by it being leaked, and/or its value to an adversary.

A common extension of the stored data fallacy is to think that data retention periods are somehow related to the risks of data being collected now and decrypted later. However, your quantum risk has nothing to do with your stored data at all - never mind how long you store it for! You actually need to think about how long into the future the data you send across a network today could be of interest to someone else in order to understand your risk. Which is a neat segue to….

Myth 4: Criminals are harvesting everyone’s data now so they can decrypt it later

There is a genuine risk that someone could collect data sent across the network, that has been encrypted using public key cryptography algorithms that are vulnerable to quantum attack. They could potentially take a copy without being detected, and at some point in the future when they have access to a sufficiently good quantum computer they could decrypt and read the contents. We can imagine scenarios where this could be an issue, where there is a need to keep such data confidential for a long period into the future.

However, to execute such an attack, often called a “harvest now, decrypt later” attack, requires significant resources and patience. You would need to be willing to invest lots of money now to collect and store encrypted data for an uncertain payoff at an unknown point in the distant future. And even if you were in a position where you could then start to decrypt the data, given the costs and time to decrypt each session, you would need to be quite selective about which data you tried to decrypt in 10-20 years time. Otherwise, for a criminal group, the results might be embarrassing if you end up with cat memes instead of data that could be monetised

This means that the business case for such activity is unlikely to make sense for a financially motivated cyber criminal, as the potential payoff is too uncertain and too far in the future. The groups doing “harvest now, decrypt later” attacks today are most likely to be well-resourced nation states, for the purposes of espionage. We can imagine examples where it would be a serious concern - for example valuable confidential IP, or the plans for a nuclear submarine. However, it is through this lens that the risk should be assessed - rather than worrying about cyber-criminal groups.

If you remember nothing else…

The important thing is that the primary risk is to asymmetric (public key) encryption. This is primarily used to protect data sent across a network - so your risk depends on what data you send across a network, and who potentially could see that data as it goes across the network. Thinking about what data you store or how long you store it for is just an irrelevant distraction.

The other potential risk is transactions that rely on digital signatures to confirm the identity of the parties. However, transactions done today are not at risk if someone has a quantum computer in the future - the threat scenario requires such a computer at the time an attacker wants to forge a signature.

Having understood your risk, the next step is to plan what you should do to mitigate this. There is another set of myths to contend with regarding potential solutions, which will be the subject of a future article.

MDR Quantum helps organisations to understand and assess their quantum risk and to respond accordingly. Our services include executive briefings, policy development, risk assessment and PQC migration strategy and planning - please reach out if you’d like to learn more about how we may be able to help.

The latest estimates for breaking RSA-2048 are around 1,000,000 physical qubits running for seven days to obtain a single private key. If we assume 5W power required per qubit, and a (bulk) power price of $0.12 per kWh, the electric bill would be approx $100k

Feel free to use #noqday if you agree :-)

Great mythbusting. The $100k+ cost per session key decryption really underscores why Q-Day framing is misleading. Most orgs are overreacting to asymmetric encryption threats while missing that their stored data usingsymmetric encryption is fine. The harvest now decrypt later threat model makes sense for nation state actors with long time horizons but doesn't justify mass panic for comercial entities. Prioritizing network transmission data over stored data is the key insight most miss.